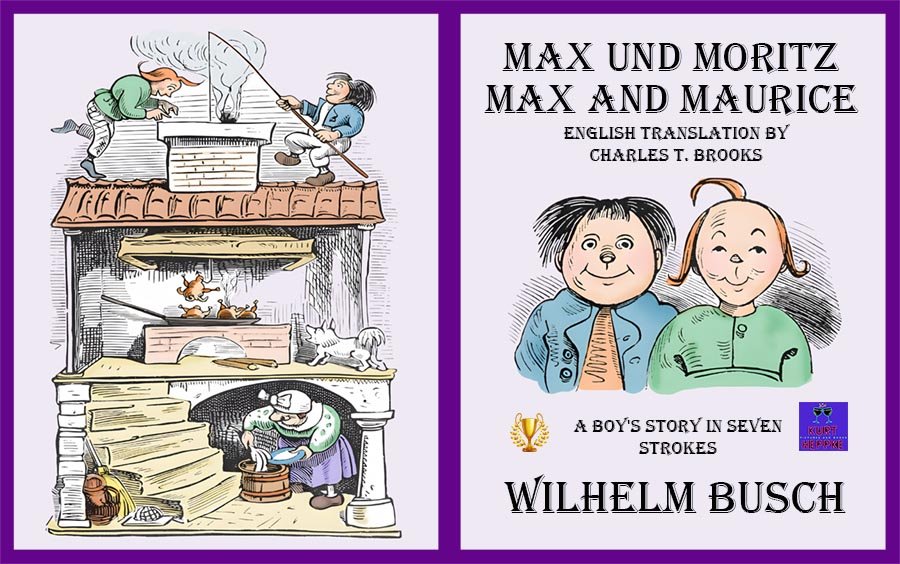

Max und Moritz Max and Maurice: A boy’s story in seven strokes

Max and Moritz – A Boy’s Story in Seven Pranks is a picture story by the German humorist poet and illustrator Wilhelm Busch.

It was first published at the end of October 1865 and is therefore one of Wilhelm Busch’s early works.

In the plot structure, it exhibits striking regularities and basic patterns in terms of content, style and aesthetic effect, which are also repeated in Wilhelm Busch’s later works.

Many of the rhymes in this picture story, such as

- „But woe, woe, woe! When I look at the end!“

- „This was the first trick, but the second follows immediately“

- … and …

- „Thank God! Now it’s over with the evil-doers!“

have become common phrases in the German language.

… and the moral of the story?

Contemporary works comparable to Wilhelm Busch’s picture story Max and Moritz usually divide people into the categories of good and evil. Parents, teachers and adults as a whole belong to the class of the good, who derive their legitimacy from punishing „bad“ children and young people for their deviations. Wilhelm Busch does not make this distinction. Busch’s child characters are almost all, without exception, malicious and aggressive. In Max and Moritz, their maliciousness is detached from any motive and is the result of a pure urge to act.

The story is one of the best-selling children’s books and has been translated into 300 languages and dialects.

Max und Moritz: eine Bubengeschichte in sieben Streichen

Max und Moritz – Eine Bubengeschichte in sieben Streichen ist eine Bildergeschichte des deutschen humoristischen Dichters und Zeichners Wilhelm Busch.

Sie wurde Ende Oktober 1865 erstveröffentlicht und zählt damit zum Frühwerk von Wilhelm Busch.

Im Handlungsgefüge weist sie auffällige Gesetzmäßigkeiten und Grundmuster inhaltlicher, stilistischer und wirkungsästhetischer Art auf, die sich auch in den späteren Arbeiten von Wilhelm Busch wiederholen.

Viele Reime dieser Bildergeschichte wie

- „Aber wehe, wehe, wehe!

- Wenn ich auf das Ende sehe!“

- „Dieses war der erste Streich,

- doch der zweite folgt sogleich“

- … und …

- „Gott sei Dank! Nun ist’s vorbei

- Mit der Übeltäterei!“

sind zu geflügelten Worten im deutschen Sprachgebrauch geworden.

… und die Moral von der Geschicht?

Mit Wilhelm Buschs Bildergeschichte Max und Moritz vergleichbare zeitgenössische Werke unterteilen die Menschen gewöhnlich in die Kategorien Gut und Böse. Eltern, Lehrer sowie Erwachsene insgesamt gehören zur Klasse der Guten, die daraus ihre Legitimation beziehen, „böse“ Kinder und Jugendliche für ihre Abweichungen zu bestrafen.

Bei Wilhelm Busch findet sich diese Unterscheidung nicht. Buschs Kindergestalten sind zwar fast alle ausnahmslos bösartig und aggressiv. Ihre Bösartigkeit ist in Max und Moritz von jeglichem Beweggrund losgelöst und Resultat eines reinen Tätigkeitsdranges.

Die Geschichte ist eines der meistverkauften Kinderbücher und wurde in 300 Sprachen und Dialekte übertragen.